Roman Road at Tupton is variously known as Ryknild Street, Rykneld Street, Ryknield Street and Icknield Street. What is today referred to as the Icknield Street road acquired the name Ryknild Street during the 12th century, when it was named by Ranulf Higdon, a monk of Chester writing in 1344 in his Polychronicon. Higdon gives the name as Rikenild Strete, which, he says, tends from the south-west to the north, and begins at St. David’s in Wales and continues across England to the mouth of the Tyne, passing Worcester, Droitwich, Birmingham, Lichfield, Derby, and Chesterfield.

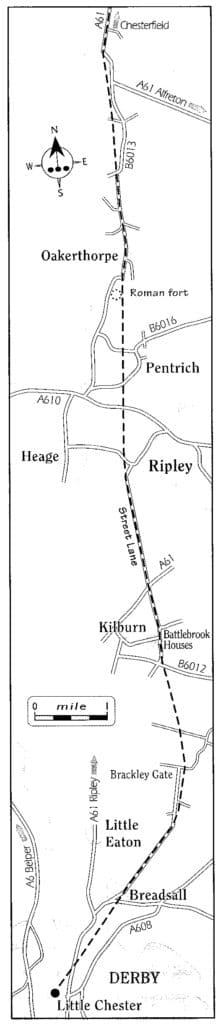

Map of section of Ryknield Street Roman road ref 4

It was described by Ivan Margary in his book ‘Roman Roads in Britain’ (3rd edition 1973). Numbered Road 18, it was divided into five (or six) sections. Its length is 112½ miles.

18d. Derby (Little Chester) to Chesterfield 21½ miles

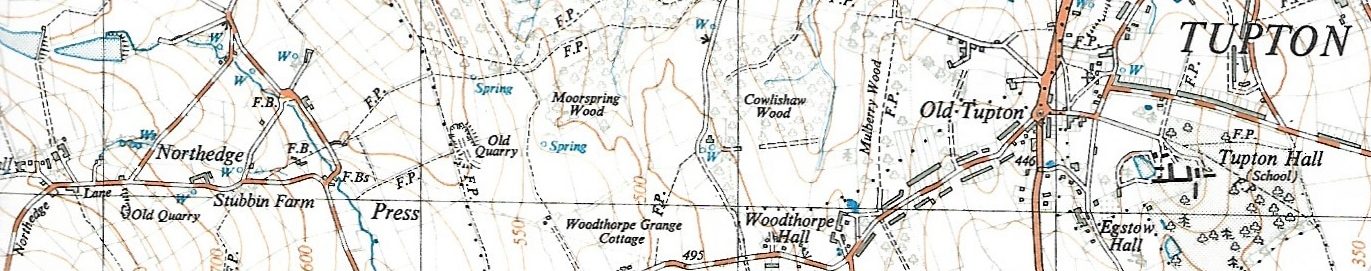

At Little Chester, Ryknild Street begins a new alignment to Morleymoor (SK384413). Its course is lost in the outskirts of Derby but is picked up by Moor Road at grid reference SK372400. It becomes Quarry Road at Morleymoor. From here the road is shown shown on Ordnance Survey Landranger and Explorer mapping as it heads north to Clay Cross. A combination of unclassified roads and cross country course brings it to the B6013 at Oakerthorpe (SK387549), which follows it – more or less – through Four Lane Ends (A615, B5035) to the A61 at Higham. The A61 follows the road closely through Clay Cross to near Hill Top Farm, where the modern road heads for Old Tupton and the Roman road makes a new direct line for the river Rother at OS grid reference SK392676.

It is unclear whether the road crossed the river at this point to approach Chesterfield from the east bank or continued through Birdholme (i.e near the modern A61). Either way the route is lost. ref 19

Roman roads were artificially made-up routes introduced to Britain by the Roman army from c.AD 43.

They facilitated both the conquest of the province and its subsequent administration. Their main purpose was to serve the Cursus Publicus, or Imperial mail service. Express messengers could travel up to 150 miles (241km) per day on the network of Roman roads throughout Britain and Europe, changing horses at wayside `mutationes’ (posting stations set every 8 miles (12.87km) on major roads) and stopping overnight at `mansiones’ (rest houses located every 20-25 miles (32km-40km).

In addition, throughout the Roman period and later, Roman roads acted as commercial routes and became foci for settlement and industry. Mausolea were sometimes built flanking roads during the Roman period while, in the Anglian and medieval periods, Roman roads often served as property boundaries.

Although a number of roads fell out of use soon after the withdrawal of Rome from the province in the fifth century AD, many have continued in use down to the present day and are consequently sealed beneath modern roads.

On the basis of construction technique, two main types of Roman road are distinguishable. The first has widely spaced boundary ditches and a broad elaborate agger comprising several layers of graded materials. The second usually has drainage ditches and a narrow simple agger of two or three successive layers. In addition to ditches and construction pits flanking the sides of the road, features of Roman roads can include central stone ribs, kerbs and culverts, not all of which will necessarily be contemporary with the original construction of the road.

With the exception of the extreme south-west of the country, Roman roads are widely distributed throughout England and extend into Wales and lowland Scotland. They are highly representative of the period of Roman administration and provide important evidence of Roman civil engineering skills as well as the pattern of Roman conquest and settlement.

A high proportion of examples exhibiting good survival are considered to be worthy of protection. ref 13